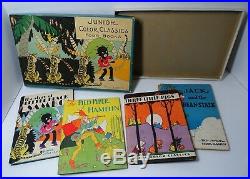

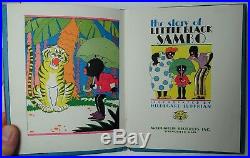

RARE Children's 4 Book Set w Box 1931 Little Black Sambo etc McLoughlin Art Deco

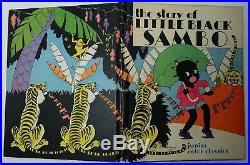

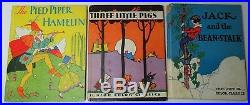

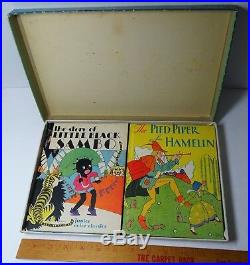

RARE Illustrated Children's Book Set. The Story of Little Black Sambo. The Pied Piper of Hamelin. For offer, a scarce book set! Fresh from a prominent estate in Upstate NY.

Never offered on the market until now. Vintage, Old, Original, Antique, NOT a Reproduction - Guaranteed!! Rare - I could not locate this for sale anywhere - I could only find one listed in an old catalog from years ago, with an asking of nearl 1,000.

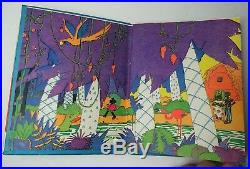

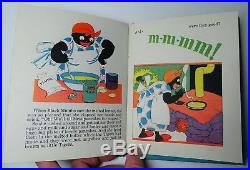

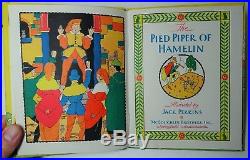

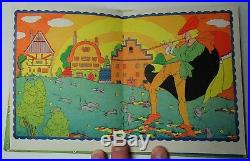

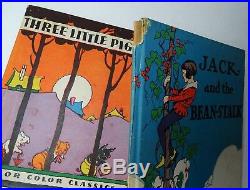

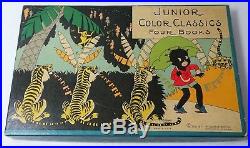

4 books (6x7.5) in the original pictorial box. Has great Art Deco illustrations in bold colors by HILDEGARD LUPPRIAN.

Piper and Jack are equally as well illustrated by Jack Perkins and H. Three Little Pigs illustrated by Carl Emil Wehde. Overall in very good condition. The box has NOT been repaired, and is quite nice. Some edge and corner wear.

The books are overall very good. Jack and beanstalk has ding to upper lh corner. Pleas e see photos for all details.

If you collect 20th century American imprints, Children's literature, Americana, Classic tales, African American, artist signed illustration art, story, history, etc. This is a treasure you will not see again! Add this to your library, or paper / ephemera collection. A typical McLoughlin Brothers publication.

Was a New York publishing firm active between 1858[1] and 1920. The company was a pioneer in color printing technologies in children's books. [2] The company specialized in retellings or bowdlerizations of classic stories for children. The artistic and commercial roots of the McLoughlin firm were first developed by John McLoughlin, Jr. (18271905) who made his younger brother Edmund McLoughlin (1833 or 4-1889) a partner in 1855. By 1886, the firm published a wide range of items, including cheap chapbooks, large folio picture books, linen books, puzzles, games, paper soldiers and paper dolls. Many of the earliest and most valuable board games in America were produced by McLoughlin Brothers of New York. McLoughlin ceased game production at this time, but continued publishing their picture books. The Story of Little Black Sambo is a children's book written and illustrated by Scottish author Helen Bannerman, and published by Grant Richards in October 1899 as one in a series of small-format books called The Dumpy Books for Children.The story was a children's favourite for more than half a century. Critics of the time observed that Bannerman presents one of the first black heroes in children's literature and regarded the book as positively portraying black characters in both the text and pictures, especially in comparison to the more negative books of that era that depicted blacks as simple and uncivilised.

[1] However, it would become an object of allegations of racism in the mid-20th century. Both text and illustrations have undergone considerable revisions since. Sambo is a South Indian boy who lives with his father and mother, named Black Jumbo and Black Mumbo, respectively.

While out walking, Sambo encounters four hungry tigers, and surrenders his colourful new clothes, shoes, and umbrella so they will not eat him. The tigers are vain and each thinks he is better dressed than the others. They chase each other around a tree until they are reduced to a pool of ghee (clarified butter). Sambo then recovers his clothes and collects the ghee, which his mother uses to make pancakes. The book's original illustrations were done by the author and simple in style, typical of most children's books, and depicted Sambo as a Southern Indian or Tamil child.

The book has thematic similarities to Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book, published in 1894, which had far more sophisticated illustrations. However, Little Black Sambo's success led to many counterfeit, inexpensive, widely available versions that incorporated popular stereotypes of "black" peoples. For example, in 1908 John R. Neill, best known for his illustration of the Oz books by L.

Frank Baum, illustrated an edition of Bannerman's story. [3] In 1932 Langston Hughes criticised Little Black Sambo, despite its being set in India, as a typical "pickaninny" storybook which was hurtful to black children, and gradually the book disappeared from lists of recommended stories for children. Cover of 1900 first US edition published by Frederick A.

In 1942, Saalfield Publishing Company released a version of Little Black Sambo illustrated by Ethel Hays. [5] In 1943, Julian Wehr created an animated version. [6] During the mid-20th century, however, some American editions of the story, including a 1950 audio version on Peter Pan Records, changed the title to the racially neutral Little Brave Sambo.Little Black Sambo (Chibikuro Sanbo) was first published in Japan by Iwanami Shoten Publishing in 1953. The book was an unlicensed version of the original, and it contained drawings by Frank Dobias that had appeared in a US edition published by Macmillan Publishers in 1927. Sambo was illustrated as an African boy rather than as an Indian boy. Although it did not contain Bannerman's original illustrations, this book was long mistaken for the original version in Japan. These are still in print.

The above description does not match with a Japanese account of why the books were terminated from publication. According to this account, The Association to Stop Racism Against Blacks launched a complaint against all major publishers in Japan that published variations of the story, and this triggered self-censorship among those publishers. The reprinting caused criticism from media outside Japan, such as The Los Angeles Times. In 1961, Whitman Publishing Company released an edition illustrated by Violet LaMont. Her colorful pictures show an Indian family wearing bright Indian clothes.

The story of the boy and tigers is as described in the above plot section. Page from 1961 Little Black Sambo.In 1996, noted illustrator Fred Marcellino observed that the story itself contained no racist overtones and produced a re-illustrated version, The Story of Little Babaji, which changes the characters' names but otherwise leaves the text unmodified. Julius Lester, in his Sam and the Tigers, also published in 1996, recast "Sam" as a hero of the mythical Sam-sam-sa-mara, where all the characters were named "Sam". A modern printing with the original title, in 2003, substituted more racially sensitive illustrations by Christopher Bing, in which, for example, Sambo is no longer so inky black. It was chosen for the Kirkus 2003 Editor's Choice list.

Some critics were still unsatisfied. Poussaint said of the 2003 publication: I don't see how I can get past the title and what it means. Trying to do'Little Black Darky' and saying,'As long as I fix up the character so he doesn't look like a darky on the plantation, it's OK. [this quote needs a citation].

In 1997, Kitaooji Shobo Publishing in Kyoto obtained formal license from the UK publisher, and republished the work under the title of Chibikuro Sambo ("Chibi" means "little" and "kuro" means black). The protagonist is depicted as a black Labrador puppy that goes for a stroll in the jungle; no humans appear in the edition. The Association To Stop Racism Against Blacks still refers to the book in this edition as discriminatory. Bannerman's original was first published with a translation of Masahisa Nadamoto by Komichi Shobo Publishing, Tokyo, in 1999.In 2004, a Little Golden Book version was published, The Boy and the Tigers, with new names and illustrations by Valeria Petrone. The boy is called Little Rajani.

Sam from Little Black Sambo appears in Jack of Fables Volume 1: The (Nearly) Great Escape. He is a prisoner of Golden Burroughs, a prison for Fables. Referenced the story of Little Black Sambo in the 1986 song "Begin the Begin": On Zenith, on the TV, tiger run around the tree. Follow the leader, run and turn into butter. It was retold as "Little Kim" in a storybook and cassette as part of the Once Upon a Time Fairy Tale Series where Sambo is called "Kim", his father Jumbo is "Tim" and his mother Mumbo is "Sim".Little Black Sambo board game (box lid). A board game was produced in 1924 and re-issued in 1945, with different artwork. Essentially the game followed the storyline, starting and ending at home. In the 1930s, Wyandotte Toys used a pickaninny caricature "Sambo" image for a dart-gun target.

An animated version of the story was produced in 1935 as part of Ub Iwerks' ComiColor series. Columbia Records issued a 1946 version on two 78 RPM records with narration by Don Lyon. [14] It was issued in a folder with artwork showing Sambo to be quite black indeed, though the narrative preserves the locale as India. In 1961, HMV Junior Record Club issued a dramatised version words by David Croft, music by Cyril Ornadel with Susan Hampshire in the title role and narrated by Ray Ellington.

An independent restaurant founded in 1957 in Lincoln City, Oregon, is named Lil' Sambo's after the fictional character. Coincidentally, a popular US restaurant chain of the 1950s through 1970s, Sambo's, borrowed characters from the book (including Sambo and the tigers) for promotional purposes, although the Sambo name was originally a combination of the founders' names and nicknames: Sam (Sam Battistone) and Bo (Newell Bohnett). [18] Nonetheless, the controversy about the book led to accusations of racism that contributed to the 1,117-restaurant[19] chain's demise in the early 1980s. [18] Images inspired by the book (now considered by some racially insensitive) were common interior decorations in the restaurants.

[20] Though portions of the original chain were renamed No Place Like Sam's to try to forestall closure, [19] all but the original restaurants in Santa Barbara, California, had closed by 1983. The original location still exists in Santa Barbara under the name Sambo's.

Zambo (or in Southern Spanish Sambo/sambo), a term used in the Spanish colonial caste system to denote a person with both African and Amerindian ancestry. Murzynek Bambo Little black Bambo by Polish writer Julian Tuwim.The Pied Piper of Hamelin (German: Rattenfänger von Hameln, also known as the Pan Piper or the Rat-Catcher of Hamelin) is the titular character of a legend from the town of Hamelin (Hameln), Lower Saxony, Germany. The legend dates back to the Middle Ages, the earliest references describing a piper, dressed in multicolored ("pied") clothing, who was a rat-catcher hired by the town to lure rats away[1] with his magic pipe.

When the citizens refuse to pay for this service, he retaliates by using his instrument's magical power on their children, leading them away as he had the rats. This version of the story spread as folklore and has appeared in the writings of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the Brothers Grimm, and Robert Browning, among others. There are many contradictory theories about the Pied Piper. Some suggest he was a symbol of hope to the people of Hamelin, which had been attacked by plague; he drove the rats from Hamelin, saving the people from the epidemic. 1592 painting of Pied Piper copied from the glass window of Marktkirche in Hamelin. The earliest known record of this story is from the town of Hamelin itself, depicted in a stained glass window created for the church of Hamelin, which dates to around 1300. Although the church was destroyed in 1660, several written accounts of the tale have survived. In 1284, while the town of Hamelin was suffering from a rat infestation, a piper dressed in multicolored ("pied") clothing appeared, claiming to be a rat-catcher.He promised the mayor a solution to their problem with the rats. The mayor, in turn, promised to pay him for the removal of the rats. According to some versions of the story, the promised sum was 1000 guilders.

The piper accepted and played his pipe to lure the rats into the Weser River, where all but one drowned. Despite the piper's success, the mayor reneged on his promise and refused to pay him the full sum (reputedly reduced to a sum of 50 guilders) even going so far as to blame the piper for bringing the rats himself in an extortion attempt. Enraged, the piper stormed out of the town, vowing to return later to take revenge. In so doing, he attracted the town's children. One hundred and thirty children followed him out of town and into a cave and were never seen again.

Depending on the version, at most three children remained behind: one was lame and could not follow quickly enough, the second was deaf and therefore could not hear the music, and the last was blind and unable to see where he was going. These three informed the villagers of what had happened when they came out from church. Other versions relate that the Pied Piper led the children to the top of Koppelberg Hill, where he took them to a beautiful land, [5] or a place called Koppenberg Mountain, [6] or Transylvania, or that he made them walk into the Weser as he did with the rats, and they all drowned. Illustration by Kate Greenaway for Robert Browning's "The Pied Piper of Hamelin".

The earliest mention of the story seems to have been on a stained-glass window placed in the Church of Hamelin c. The window was described in several accounts between the 14th and 17th centuries. [8] It was destroyed in 1660. Based on the surviving descriptions, a modern reconstruction of the window has been created by historian Hans Dobbertin.

It features the colorful figure of the Pied Piper and several figures of children dressed in white. This window is generally considered to have been created in memory of a tragic historical event for the town. Also, Hamelin town records start with this event. The earliest written record is from the town chronicles in an entry from 1384 which states: It is 100 years since our children left.

Although research has been conducted for centuries, no explanation for the historical event is universally accepted as true. In any case, the rats were first added to the story in a version from c. 1559 and are absent from earlier accounts. The Pied Piper leads the children out of Hamelin.

A number of theories suggest that children died of some natural causes such as disease or starvation[11] and that the Piper was a symbolic figure of Death. Analogous themes which are associated with this theory include the Dance of Death, Totentanz or Danse Macabre, a common medieval trope. Some of the scenarios that have been suggested as fitting this theory include that the children drowned in the river Weser, were killed in a landslide or contracted some disease during an epidemic. Another modern interpretation reads the story as alluding to an event where Hamelin children were lured away by a pagan or heretic sect to forests near Coppenbrügge (the mysterious Koppen "hills" of the poem) for ritual dancing where they all perished during a sudden landslide or collapsing sinkhole. Added speculation on the migration is based on the idea that by the 13th century the area had too many people resulting in the oldest son owning all the land and power (majorat), leaving the rest as serfs.

She states further that this may account for the lack of records of the event in the town chronicles. [9] In his book The Pied Piper: A Handbook, Wolfgang Mieder states that historical documents exist showing that people from the area including Hamelin did help settle parts of Transylvania. [14] Transylvania had suffered under lengthy Mongol invasions of Central Europe, led by two grandsons of Genghis Khan and which date from around the time of the earliest appearance of the legend of the piper, the early 13th century. In the version of the legend posted on the official website for the town of Hamelin, another aspect of the emigration theory is presented.

Among the various interpretations, reference to the colonization of East Europe starting from Low Germany is the most plausible one: The "Children of Hameln" would have been in those days citizens willing to emigrate being recruited by landowners to settle in Moravia, East Prussia, Pomerania or in the Teutonic Land. It is assumed that in past times all people of a town were referred to as "children of the town" or "town children" as is frequently done today. The "Legend of the children's Exodus" was later connected to the "Legend of expelling the rats". This most certainly refers to the rat plagues being a great threat in the medieval milling town and the more or less successful professional rat catchers. Historian Ursula Sautter, citing the work of linguist Jurgen Udolph, offers this hypothesis in support of the emigration theory.

"After the defeat of the Danes at the Battle of Bornhöved in 1227, " explains Udolph, the region south of the Baltic Sea, which was then inhabited by Slavs, became available for colonization by the Germans. " The bishops and dukes of Pomerania, Brandenburg, Uckermark and Prignitz sent out glib "locators, medieval recruitment officers, offering rich rewards to those who were willing to move to the new lands. Thousands of young adults from Lower Saxony and Westphalia headed east. And as evidence, about a dozen Westphalian place names show up in this area. Indeed there are five villages called Hindenburg running in a straight line from Westphalia to Pomerania, as well as three eastern Spiegelbergs and a trail of etymology from Beverungen south of Hamelin to Beveringen northwest of Berlin to Beweringen in modern Poland. Udolph favors the hypothesis that the Hamelin youths wound up in what is now Poland. [18] Genealogist Dick Eastman cited Udolph's research on Hamelin surnames that have shown up in Polish phonebooks. Linguistics professor Jürgen Udolph says that 130 children did vanish on a June day in the year 1284 from the German village of Hamelin (Hameln in German). Udolph entered all the known family names in the village at that time and then started searching for matches elsewhere. He found that the same surnames occur with amazing frequency in the regions of Prignitz and Uckermark, both north of Berlin. He also found the same surnames in the former Pomeranian region, which is now a part of Poland.Udolph surmises that the children were actually unemployed youths who had been sucked into the German drive to colonize its new settlements in Eastern Europe. The Pied Piper may never have existed as such, but, says the professor, There were characters known as lokators who roamed northern Germany trying to recruit settlers for the East. Some of them were brightly dressed, and all were silver-tongued.

Professor Udolph can show that the Hamelin exodus should be linked with the Battle of Bornhöved in 1227 which broke the Danish hold on Eastern Europe. That opened the way for German colonization, and by the latter part of the thirteenth century there were systematic attempts to bring able-bodied youths to Brandenburg and Pomerania. The settlement, according to the professor's name search, ended up near Starogard in what is now northwestern Poland. A village near Hamelin, for example, is called Beverungen and has an almost exact counterpart called Beveringen, near Pritzwalk, north of Berlin and another called Beweringen, near Starogard. Local Polish telephone books list names that are not the typical Slavic names one would expect in that region. Instead, many of the names seem to be derived from German names that were common in the village of Hamelin in the thirteenth century. In fact, the names in today's Polish telephone directories include Hamel, Hamler and Hamelnikow, all apparently derived from the name of the original village. Fourteenth-century Decan Lude chorus book. Decan Lude of Hamelin was reported c.1384, to have in his possession a chorus book containing a Latin verse giving an eyewitness account of the event. 144050 gives an early German account of the event, rendered in the following form in an inscription on a house in Hamelin:[21]. Dorch einen piper mit allerley farve bekledet gewesen cxxx kinder verledet binnen hameln geboren.

To calvarie bi den koppen verloren. In the year 1284 on the day of [Saints] John and Paul on 26th June. 130 children born in Hamelin were led away by a piper [clothed] in many colours.

To [their] Calvary near the Koppen, [and] lost. According to author Fanny Rostek-Lühmann this is the oldest surviving account. Koppen (High German Kuppe, meaning a knoll or domed hill) seems to be a reference to one of several hills surrounding Hamelin. Which of them was intended by the manuscript's author remains uncertain. Somewhere between 1559 and 1565, Count Froben Christoph von Zimmern included a version in his Zimmerische Chronik.

[23] This appears to be the earliest account which mentions the plague of rats. Von Zimmern dates the event only as "several hundred years ago" (vor etlichen hundert jarn [sic]), so that his version throws no light on the conflict of dates (see next paragraph).Another contemporary account is that of Johann Weyer in his De praestigiis daemonum (1563). Some theories have linked the disappearance of the children to Mass Psychogenic Illness in the form of Dancing mania.

Dancing mania outbreaks occurred during the 13th century, including one in 1237 in which a large group of children travelled from Erfurt to Arnstadt (about 20 km), jumping and dancing all the way, [25] in marked similarity to the legend of the Pied Piper of Hamelin, which originated at around the same time. These theories see the unnamed Piper as their leader or a recruiting agent. The townspeople made up this story (instead of recording the facts) to avoid the wrath of the church or the king. William Manchester's A World Lit Only by Fire places the events in 1484, 100 years after the written mention in the town chronicles that "It is 100 years since our children left", and further proposes that the Pied Piper was a psychopathic paedophile. Although for the time period it is highly improbable that one man could abduct so many children undetected.Furthermore, nowhere in the book does Manchester offer proof of his description of the facts as he presents them. He makes similar assertions regarding other legends, also without supporting evidence.

See also: Pied Piper of Hamelin in popular culture. In 1803, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote a poem based on the story that was later set to music by Hugo Wolf. Goethe also incorporated references to the story in his version of Faust. The first part of the drama was first published in 1808 and the second in 1832.

Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm, known as the Brothers Grimm, drawing from eleven sources, included the tale in their collection Deutsche Sagen (first published in 1816). According to their account, two children were left behind as one was blind and the other lame so neither could follow the others. The rest became the founders of Siebenbürgen (Transylvania).

Using the Verstegan version of the tale and adopting the 1376 date, Robert Browning wrote a poem of that name which was published in his Dramatic Lyrics (1842). [29] Browning's retelling in verse is notable for its humour, wordplay, and jingling rhymes. [citation needed]according to whom? Viktor Dyk's Krysa (The Rat-Catcher), published in 1915, retells the story in a slightly darker, more enigmatic way. The short novel also features the character of Faust. The Pied Piper (16 September 1933) is a short animated film based on the story, produced by Walt Disney Productions, directed by Wilfred Jackson, and released as a part of the Silly Symphonies series. It stars the voice talents of Billy Bletcher as the Mayor of Hamelin. Van Johnson starred as the Piper in NBC studios' adaptation: The Pied Piper of Hamelin (1957). The Pied Piper is a 1972 British film directed by Jacques Demy and starring Jack Wild, Donald Pleasence, and John Hurt and featuring Donovan and Diana Dors.In 1986 Jií Bárta made an animated movie The Pied Piper based more on the above-mentioned story by Viktor Dyk; the movie was accompanied by the rock music by Michal Pavlíek. In 1989 W11 Opera premiered Koppelberg, an opera they commissioned from composer Steve Gray and lyricist Norman Brooke; the work was based on the Robert Browning poem. Maythil Radhakrishnan's 1995 short story'Sangeetham oru samayakalayanu' (Music is a Time-art) revolves around a sanitary inspector's assumption that links pied piper's story and bubonic plague of 14th century Europe. China Miéville's 1998 London-set novel King Rat centers on the ancient rivalry between the rats (some of whom are portrayed as having humanlike characteristics) and the Pied Piper, who appears in the novel as a mysterious musician named Pete who infiltrates the local club-music scene. The cast of Peanuts did their own version of the tale in the direct-to-DVD special It's the Pied Piper, Charlie Brown (2000), which was the final special to have the involvement of original creator Charles Schulz.

Demons and Wizards' first album, Demons and Wizards (2000), includes a track called "The Whistler" which recounts the tale of Pied Piper. Terry Pratchett's 2001 young-adult novel, The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents, parodies the legend from the perspective of the rats, the piper, and their handler.

The 2003 television film The Electric Piper, set in the United States in the 1960s, depicts the piper as a psychedelic rock guitarist modeled after Jimi Hendrix. The Pied Piper of Hamelin was adapted in Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child where it uses jazz music. The episode featured Wesley Snipes as the Pied Piper and the music performed by Ronnie Laws as well as the voices of Samuel L.

Jackson as the Mayor of Hamelin, Grant Shaud as the Mayor's assistant Toadey (pronounced toe-day), John Ratzenberger and Richard Moll as respective guards Hinky and Dinky. In the anime adaptation of the Japanese light novel series, Problem Children Are Coming from Another World, Aren't They? (2013), a major story revolves around the "false legend" of Pied Piper of Hamelin. The adaptation speaks in great length about the original source and the various versions of the story that sprang up throughout the years. It is stated that Weser, the representation of Natural Disaster, was the true Piper of Hamelin (meaning the children were killed by drowning or landslides).

In 2015, a South Korean horror movie title The Piper was released. It is a loose adaptation of the Brothers Grimm tale where the Pied Piper uses the rats for his revenge to kill all the villagers except for the children whom he traps in a cave. The short story "The Rat King" by John Connolly, first included in the 2016 edition of his novel The Book of Lost Things, is a fairly faithful adaptation of the legend, but with a new ending. It was adapted for BBC Radio 4 and first broadcast on 28 October 2016. In the American TV series Once Upon a Time[37], the Pied Piper is revealed to be Peter Pan, who is using pipes to call out to "lost boys" and take them away from their homes. Merriam-Webster definitions of pied piper. A charismatic person who attracts followers.A musician who attracts mass. A leader who makes irresponsible promises.

In linguistics, pied-piping is the common name for the ability of question words and relative pronouns to drag other words along with them when brought to the front, as part of the phenomenon called Wh-movement. For example, in For whom are the pictures? ", the word "for" is pied-piped by "whom" away from its declarative position ("The pictures are for me"), and in "The mayor, pictures of whom adorn his office walls" both words "pictures of are pied-piped in front of the relative pronoun, which normally starts the relative clause. Some researchers believe that the tale has inspired the common English phrase "pay the piper", [39] although the phrase is actually a contraction of the English proverb "he who pays the piper calls the tune" which simply means that the person paying for something is the one who gets to say how it should be done. Present-day Hamelin and the Pied Piper in modern times.

The present-day City of Hamelin continues to maintain information about the Pied Piper legend and possible origins of the story on its website. Interest in the city's connection to the story remains so strong that in 2009, Hamelin held a tourist festival to mark the 725th anniversary of the disappearance of the town's earlier children. [41] The eerie nature of such a celebration was enough to warrant an article in the Fortean Times, a print magazine devoted to odd occurrences, legends, cryptozoology and all things strange which are known now as Forteana[42] The article noted that even to this day, there is prohibition against playing music or dancing upon the Bungelosenstrasse ("street without drums"), the street where the children were purported to have last been seen before they disappeared or left the town. There is even a building, popular with visitors, that is called "the rat catcher's house" although it bears no connection to the Rat-Catcher version of the legend. Indeed, the Rattenfängerhaus is instead, associated with the story due to the earlier inscription upon its facade mentioning the legend. The house was built much later in 1602 and 1603.It is now a Hamelin City-owned restaurant with a pied piper theme throughout. [43] The city also maintains an online shop with rat-themed merchandise as well as offering an officially licensed Hamelin Edition of the popular board game Monopoly which depicts the legendary Piper on the cover. In addition to the recent milestone festival, each year the city marks June 26 as "Rat Catcher's Day". In the United States, a similar holiday for Exterminators based on Rat Catcher's Day has failed to catch on and is marked on July 22.

List of literary accounts of the Pied Piper. Pied Piper of Hamelin in popular culture. Three little pigs 1904 straw house. The wolf blows down the straw house in a 1904 adaptation of the story. Illustration by Leonard Leslie Brooke.The Three Little Pigs is a fable about three pigs who build three houses of different materials. A big bad wolf blows down the first two pigs' houses, made of straw and sticks respectively, but is unable to destroy the third pig's house, made of bricks. Printed versions date back to the 1840s, but the story itself is thought to be much older.

The phrases used in the story, and the various morals drawn from it, have become embedded in Western culture. Many versions of The Three Little Pigs have been recreated or have been modified over the years, sometimes making the wolf a kind character. It is a type 124 folktale in the AarneThompson classification system. Jacobs, English Fairy Tales (New York, 1895).

The Three Little Pigs was included in The Nursery Rhymes of England London and New York, c. [1] The story in its arguably best-known form appeared in English Fairy Tales by Joseph Jacobs, first published in 1890 and crediting Halliwell as his source. [2] The story begins with the title characters being sent out into the world by their mother, to "seek out their fortune". The first little pig builds a house of straw, but a wolf blows it down and devours him. The second little pig builds a house of sticks, which the wolf also blows down, and the second little pig is also devoured. Little pig, little pig, let me come in. Not by the hair on my chinny chin chin. Then I'll huff, and I'll puff, and I'll blow your house in. The third little pig builds a house of bricks. The wolf fails to blow down the house. He then attempts to trick the pig out of the house by asking to meet him at various places, but he is outwitted each time. Finally, the wolf resolves to come down the chimney, whereupon the pig catches the wolf in a cauldron of boiling water, slams the lid on, then cooks and eats him. The story uses the literary rule of three, expressed in this case as a "contrasting three", as the third pig's brick house turns out to be the only one which is adequate to withstand the wolf.[4] Variations of the tale appeared in Uncle Remus: His Songs and Sayings in 1881. The story also made an appearance in Nights with Uncle Remus in 1883, both by Joel Chandler Harris, in which the pigs were replaced by Brer Rabbit. Andrew Lang included it in The Green Fairy Book, published in 1892, but did not cite his source. In contrast to Jacobs's version, which left the pigs nameless, Lang's retelling cast the pigs as Browny, Whitey, and Blacky.

It also set itself apart by exploring each pig's character and detailing interaction between them. The antagonist of this version is a fox, not a wolf.

The pigs' houses are made either of mud, cabbage, or brick. Blacky, the third pig, rescues his brother and sister from the fox's den after the fox has been defeated. Main article: The Three Little Pigs (film). The most well-known version of the story is an award-winning 1933 Silly Symphony cartoon, which was produced by Walt Disney. The production cast the title characters as Fifer Pig, Fiddler Pig, and Practical Pig.

The first two are depicted as both frivolous and arrogant. The story has been somewhat softened. The first two pigs still get their houses blown down, but escape from the wolf. Also, the wolf is not boiled to death but simply burns his behind and runs away. Three sequels soon followed in 1934, 1936 and 1939 respectively.

Fifer Pig, Fiddler Pig, Practical Pig and the Big Bad Wolf appeared in the 2001 series Disney's House of Mouse in many episodes, and again in Mickey's Magical Christmas: Snowed in at the House of Mouse. The three pigs can be seen in Walt Disney Parks and Resorts as greetable characters. Warner Brothers and MGM versions. In 1942, there was a Merrie Melodies version made that was a serious musical treatment, plus the usual Friz Freleng visual humor.

It parodies both the Disney version, and Fantasia itself. Other versions of the tale were also made. One was an MGM Tex Avery cartoon named Blitz Wolf, a 1942 wartime version with the Wolf as a Nazi.Another animated spoof was a 1952 Warner Brothers cartoon called The Turn-Tale Wolf, directed by Robert McKimson. This cartoon tells the story from the wolf's point of view and makes the pigs out to be the villains. Another Warner Brothers spoof was Friz Freleng's The Three Little Bops (1957), which depicts the three little pigs as jazz musicians who refuse to let the wolf join their band. In 1953, Tex Avery did a Droopy cartoon, "The Three Little Pups". In it, the wolf is a Southern-accented dog catcher (voiced by Daws Butler) trying to catch Droopy and his brothers, Snoopy and Loopy, to put in the dog pound.

Though successfully blowing the first two houses down, he meets his match when he fails to blow down Droopy's house of bricks. The dog catcher makes several failed attempts to destroy the house and catch the pups.

His last failed attempt ended with him "going to television" where he is playing a cowboy on the TV show the pups were watching. The 1989 parody The True Story of the 3 Little Pigs! Is presented as a first-person narrative by the wolf, who portrays the entire incident as a misunderstanding; he had gone to the pigs to borrow some sugar, had destroyed their houses in a sneezing fit, ate the first two pigs to not waste food (since they'd died in the house collapse anyway), and was caught attacking the third pig's house after the pig had continually insulted him. The 1992 Green Jellö song, Three Little Pigs (and its claymation music video) sets the story in Los Angeles. The wolf drives a Harley Davidson motorcycle, the first little pig is an aspiring guitarist, the second is a cannabis smoking, dumpster diving evangelist and the third holds a Master of Architecture degree from Harvard University.In the end, with all three pigs barricaded in the brick house, the third pig calls 9-1-1. John Rambo is dispatched to the scene, and kills the wolf with a machine gun.

The 1993 children's book The Three Little Wolves and the Big Bad Pig inverts the cast and makes a few changes to the plot: the wolves build a brick house, then a concrete house, then a steel house, and finally a house of flowers. The pig is unable to blow the houses down, destroying them by other means, but eventually gives up his wicked ways when he smells the scent of the flower house, and becomes friends with the wolves.

The three pigs and the wolf appear in the four Shrek films, and the specials Shrek the Halls and Scared Shrekless. In 2003, the Flemish company Studio 100 created a musical called Three Little Pigs (Dutch: De 3 Biggetjes), which follows the three daughters of the pig with the house of stone with new original songs, introducing a completely new story loosely based on the original story.

The musical was specially written for the band K3, who play the three little pigs, Pirky, Parky and Porky (Dutch: Knirri, Knarri and Knorri). In 2014, Peter Lund let the three little pigs live together in a village in the musical Grimm with Little Red Riding Hood and other fairy tale characters. In 2015, Saturn Animation Studio, Canada, produced an interactive adaptation of "Three Little Pigs" for all mobile devices.

Jack and the Beanstalk Giant - Project Gutenberg eText 17034. Illustration by Arthur Rackham, 1918, in English Fairy Tales by Flora Annie Steel. Jack and the Giant man.

AT 328 ("The Treasures of the Giant"). Benjamin Tabart, The History of Jack and the Bean-Stalk (1807). Joseph Jacobs, English Fairy Tales (1890). "Jack and the Beanstalk" is an English fairy tale.

It appeared as "The Story of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean" in 1734[1] and as Benjamin Tabart's moralised "The History of Jack and the Bean-Stalk" in 1807. [2] Henry Cole, publishing under pen name Felix Summerly, popularised the tale in The Home Treasury (1845), [3] and Joseph Jacobs rewrote it in English Fairy Tales (1890). [4] Jacobs' version is most commonly reprinted today, and is believed to be closer to the oral versions than Tabart's because it lacks the moralising. "Jack and the Beanstalk" is the best known of the "Jack tales", a series of stories featuring the archetypal Cornish and English hero and stock character Jack. According to researchers at the universities in Durham and Lisbon, the story originated more than 5,000 years ago, based on a widespread archaic story form which is now classified by folklorists as ATU 328 The Boy Who Stole Ogre's Treasure.

Jack is a young, poor boy living with his widowed mother and a dairy cow, on a farm cottage. The cow's milk was their only source of income. During the night, the magic beans cause a gigantic beanstalk to grow outside Jack's window. The next morning, Jack climbs the beanstalk to a land high in the sky. He finds an enormous castle and sneaks in. He smells that Jack is nearby, and speaks a rhyme. I smell the blood of an English man. Be he alive, or be he dead. I'll grind his bones to make my bread. In the versions in which the giant's wife (the giantess) features, she persuades him that he is mistaken and helps Jack hide.When the giant falls asleep. Jack steals a bag of gold coins and makes his escape down the beanstalk.

Jack climbs the beanstalk twice more. He learns of other treasures and steals them when the giant sleeps: first a goose that lays golden eggs, then a magic harp that plays by itself. The giant wakes when Jack leaves the house with the harp and chases Jack down the beanstalk. Jack calls to his mother for an axe and before the giant reaches the ground, cuts down the beanstalk, causing the giant to fall to his death. Jack and his mother live happily ever after with the riches that Jack acquired.

In Walter Crane's woodcut the harp reaches out to cling to the vine. "The Story of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean" was published in the 1734 second edition of Round About Our Coal-Fire. [1] In 1807, Benjamin Tabart published The History of Jack and the Bean Stalk, but the story is certainly older than these accounts.According to researchers at Durham University and the Universidade Nova de Lisboa, the story originated more than 5,000 years ago. In some versions of the tale, the giant is unnamed, but many plays based on it name him Blunderbore. One giant of that name appears in the 18th-century "Jack the Giant Killer".

In "The Story of Jack Spriggins" the giant is named Gogmagog. I smell the blood of an Englishman" appears in William Shakespeare's early 17th-century King Lear in the form "Fie, foh, and fum, I smell the blood of a British man. " (Act 3, Scene 4), [8] and something similar also appears in "Jack the Giant Killer. "Jack and the Beanstalk" is an Aarne-Thompson tale-type 328, The Treasures of the Giant, which includes the Italian "Thirteenth" and the French "How the Dragon was Tricked" tales. Christine Goldberg argues that the Aarne-Thompson system is inadequate for the tale because the others do not include the beanstalk, which has analogies in other types[9] (a possible reference to the genre anomaly).

The Brothers Grimm drew an analogy between this tale and a German fairy tale, "The Devil With the Three Golden Hairs". The devil's mother or grandmother acts much like the giant's wife, a female figure protecting the child from the evil male figure. In other versions he is said to have married a princess.

This is found in few other tales, such as some variants of "Vasilisa the Beautiful". The original story portrays a "hero" gaining the sympathy of a man's wife, hiding in his house, robbing, and finally killing him. In Tabart's moralised version, a fairy woman explains to Jack that the giant had robbed and killed his father justifying Jack's actions as retribution. [13] Andrew Lang follows this version in the Red Fairy Book of 1890. Jacobs gave no justification because there was none in the version he had heard as a child and maintained that children know that robbery and murder are wrong without being told in a fairy tale, but did give a subtle retributive tone to it by making reference to the giant's previous meals of stolen oxen and young children. Many modern interpretations have followed Tabart and made the giant a villain, terrorising smaller folk and stealing from them, so that Jack becomes a legitimate protagonist. For example, the 1952 film starring Abbott and Costello the giant is blamed for poverty at the foot of the beanstalk, as he has been stealing food and wealth and the hen that lays golden eggs originally belonged to Jack's family. In other versions it is implied that the giant had stolen both the hen and the harp from Jack's father. Brian Henson's 2001 TV miniseries Jack and the Beanstalk: The Real Story not only abandons Tabart's additions but vilifies Jack, reflecting Jim Henson's disgust at Jack's unscrupulous actions. Jack and the Beanstalk (1917). The first film adaptation was made in 1902 by Edwin S. Porter for the Edison Manufacturing Company.Walt Disney made a short of the same name in 1922, and a separate adaptation titled Mickey and the Beanstalk in 1947 as part of Fun and Fancy Free. This adaptation of the story put Mickey Mouse in the role of Jack, accompanied by Donald Duck, and Goofy. Mickey, Donald, and Goofy live on a farm in "Happy Valley", so called because it is always green and prosperous thanks to the magical singing from an enchanted golden harp in a castle, until one day it mysteriously disappears during a dark storm, resulting in the valley being plagued by a severe drought.

Times become so hard for Mickey and his friends that soon they have nothing to eat except one loaf of bread. Mickey trades in the cow (which Donald was going to kill for food) for the magic beans. Donald throws the beans on the floor and down a knothole in a fit of rage, and the beanstalk sprouts that night, lifting the three of them into the sky while they sleep. In the magical kingdom, Mickey, Donald, and Goofy help themselves to a sumptuous feast. This rouses the ire of the giant (named "Willie" in this version), who captures Donald and Goofy and locks them in a box, and it is up to Mickey to find the keys to unlock the box and rescue them as well as the harp which they also find in the giant's possession.

The film villainizes the giant by blaming Happy Valley's hard times on Willy's theft of the magic harp, without which song the land withers; unlike the harp of the original tale, this magic harp wants to be rescued from the giant, assists the heroes as best she can, and the hapless heroes return her to her rightful place and Happy Valley to its former glory. This version of the fairy tale was narrated (as a segment of Fun and Fancy Free) by Edgar Bergen, and later (by itself as a short) by Sterling Holloway. Walt Disney Animation Studios were to do another adaptation of the fairy tale called Gigantic. Tangled director Nathan Greno was to direct and it was set to be released in late 2020, [16] however, it was reported on October 10, 2017, that the studio had made the decision to cancel the film after struggling creatively with it.

Adapted the story into three Merrie Melodies cartoons. Friz Freleng directed Jack-Wabbit and the Beanstalk (1943), Chuck Jones directed Beanstalk Bunny (1955), and Freleng directed Tweety and the Beanstalk (1957). The 1952 Abbott and Costello adaptation was not the only time a comedy team was involved with the story. The Three Stooges had their own five-minute animated retelling, titled Three Jacks and a Beanstalk (1965). In 1967, Hanna-Barbera produced a live action version of Jack and the Beanstalk, with Gene Kelly as Jeremy the Peddler (who trades his magic beans for Jack's cow), Bobby Riha as Jack, Dick Beals as Jack's singing voice, Ted Cassidy as the voice of the animated giant, Janet Waldo as the voice of the animated Princess Serena, Marni Nixon as Serena's singing voice, and Marian McKnight as Jack's mother.

[18] The songs were written by Sammy Cahn and Jimmy Van Heusen. [19] Kelly also directed the Emmy Award-winning film. Gisaburo Sugii directed a feature-length anime telling of the story released in 1974, titled Jack to Mame no Ki. The film, a musical, was produced by Group TAC and released by Nippon Herald. The writers introduced a few new characters, including Jack's comic-relief dog, Crosby, and Margaret, a beautiful princess engaged to be married to the giant (named "Tulip" in this version) due to a spell being cast over her by the giant's mother (an evil witch called Madame Hecuba).Jack, however, develops a crush on Margaret, and one of his aims in returning to the magic kingdom is to rescue her. The film was dubbed into English, with legendary voice talent Billie Lou Watt voicing Jack, and received a very limited run in U. It was later released on VHS (now out of print) and aired several times on HBO in the 1980s. However, it is now available on DVD with both English and Japanese dialogue. Michael Davis directed the 1994 adaptation, titled Beanstalk, starring J.

Daniels as Jack and Stuart Pankin as the giant. The film was released by Moonbeam Entertainment, the children's video division of Full Moon Entertainment. Wolves, Witches and Giants Episode 9 of Season 1, Jack and the Beanstalk, broadcast on 19 October 1995, has Jack's mother chop down the beanstalk and the giant plummet through the earth to Australia. The hen that Jack has stolen fails to lay any eggs and ends up "in the pot by Sunday", leaving Jack and his mother to live in reduced circumstances for the rest of their lives. The Jim Henson Company did a TV miniseries adaptation of the story as Jim Henson's Jack and the Beanstalk: The Real Story (directed by Brian Henson) which reveals that Jack's theft from the giant was completely unmotivated, with the giant Thunderdell (played by Bill Barretta) being a friendly, welcoming individual, and the giant's subsequent death was caused by Jack's mother cutting the beanstalk down rather than Jack himself. The film focuses on Jack's modern-day descendant Jack Robinson (played by Matthew Modine) who learns the truth after the discovery of the giant's bones and the last of the five magic beans, Jack subsequently returning the goose and harp to the giants' kingdom. An episode of Mickey Mouse Clubhouse called Donald and the Beanstalk, Donald Duck accidentally swapped his pet chicken with Willie the Giant for a handful of magic beans. Avalon Family Entertainment's 2009 Jack and the Beanstalk is low-budget live-action adaptation starring Christopher Lloyd, Chevy Chase, James Earl Jones, Gilbert Gottfried, Katey Sagal, Wallace Shawn and Chloë Grace Moretz.Jack is played by Colin Ford. Film directed by Bryan Singer and starring Nicholas Hoult as Jack is titled Jack the Giant Slayer and was released in March 2013. [21] In this tale Jack climbs the beanstalk to save a princess. Animation's direct-to-DVD film Tom and Jerry's Giant Adventure is set to be based on the fairy tale.

In the 2014 film Into the Woods, and the musical of the same name, one of the main characters, Jack (Daniel Huttlestone) climbs a beanstalk, much like in the original version. He acquires a golden harp, a goose that lays golden eggs, and several gold pieces. The story goes on as it does in the original fairy tale, but continues afterwards showing what happens after you get your happy ending. In this adaptation, the giant's vengeful wife (Frances de la Tour) attacks the kingdom to find and kill Jack as revenge for him murdering her husband where some characters were killed during her rampage. The giant's wife is eventually killed by the surviving characters in the story.

The story is the basis of the similarly titled traditional British pantomime, wherein the Giant is certainly a villain, Jack's mother the Dame, and Jack the Principal Boy. Jack of Jack and the Beanstalk is the protagonist of the comic book Jack of Fables, a spin-off of Fables, which also features other elements from the story, such as giant beanstalks and giants living in the clouds. Gilligan's Island did a adaptation/dream sequence in which Gilligan tries to take oranges from a giant Skipper and fails; (the part of the little Gilligan chased by the giant was played by Bob Denver's 7 year old son Patrick Denver).Roald Dahl rewrote the story in a more modern and gruesome way in his book Revolting Rhymes (1982), where Jack initially refuses to climb the beanstalk and his mother is thus eaten when she ascends to pick the golden leaves at the top, with Jack recovering the leaves himself after having a thorough wash so that the giant cannot smell him. In the 2016 television adaptation of Revolting Rhymes, Jack lives next door to Cinderella and is in love with her.

[23] The story of Jack and the Beanstalk is also referenced in Dahl's The BFG, in which the evil giants are all afraid of the "giant-killer" Jack, who is said to kill giants with his fearsome beanstalk (although none of the giants appear to know how Jack uses it against them, the context of a nightmare one of the giants has about Jack suggesting that they think he wields the beanstalk as a weapon). James Still published Jack and the Wonder Beans (1977, republished 1996) an Appalachian variation on the Jack and the Beanstalk tale.

Jack trades his old cow to a gypsy for three beans that are guaranteed to feed him for his entire life. It has been adapted as a play for performance by children. In 1973 the story was adapted, as The Goodies and the Beanstalk, by the BBC television series The Goodies. An arcade video game, Jack the Giantkiller, was released by Cinematronics in 1982 and is based on the story.

Players control Jack, and must retrieve a series of treasures a harp, a sack of gold coins, a golden goose and a princess and eventually defeat the giant by chopping down the beanstalk. An episode of Challenge of the Superfriends titled "Fairy Tale of Doom" has the Legion of Doom using Toyman's newest invention, a projector like device to trap the Superfriends inside pages of children's fairy tales.

Toyman traps Hawkman in this story. An episode of The Super Mario Bros.Entitled "Mario and the Beanstalk", does a retelling with Bowser as the giant (there is no explanation as to how he becomes a giant). In The Magic School Bus episode "Gets Planted", the class put on a school production of Jack and the Beanstalk, with Phoebe starring as the beanstalk after Ms. Frizzle turned her into a bean plant. Jack and Beanstalk was featured in Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child where Jack is voiced by Wayne Collins and the giant is voiced by Tone Loc. The story is in an African-American style.

Stephen Sondheim's 1986 musical Into the Woods (and the 2014 film of the same name), features Jack, originally portrayed by Ben Wright, along with several other fairy tale characters. In the second half of the musical, the giant's wife climbs down a second (inadvertently planted) beanstalk to exact revenge for her husband's death, furious at Jack's betrayal of her hospitality. The Giantess then causes the deaths of Jack's mother and other important characters before being finally killed by Jack. Bart Simpson plays the role of the main character in a Simpsons video game The Simpsons: Bart & the Beanstalk.ABC's Once Upon a Time debuts their spin on the tale in the episode "Tiny" of Season Two, where Jack, now a female named Jacqueline (known as Jack) is played by Cassidy Freeman and the giant named Anton is played by Jorge Garcia. In this adaptation, Jack is portrayed as a villainous character. In Season Seven, a new iteration of Jack (portrayed by Nathan Parsons) is a recurring character and Henry Mills' first friend in the New Enchanted Forest.

Hé débuts in "The Eighth Witch". In Hyperion Heights, he is cursed as Nick Branson and is a lawyer and Lucy's fake father. The story was adapted in 2012 by software maker Net Entertainment and made into a slot machine game. Mark Knopfler sang a song, "After the Beanstalk", in his 2012 album Privateering.

Snips, Snails, and Dragon Tails, an Order of the Stick print book, contains an adaptation in the Sticktales section. Elan is Jack, Roy is the giant, Belkar is the golden goose, and Vaarsuvius is the wizard who sells the beans. Haley also appears as an agent sent to steal the golden goose, and Durkin as a dwarf neighbor with the comic's stereotypical fear of tall plants.

In the Season 3 premiere episode of Barney and Friends titled "Shawn and the Beanstalk", Barney the Dinosaur and the gang tell their version of Jack and the Beanstalk which was all told in rhyme. In the animated movie Puss in Boots, the classic theme appears again. The magic beans play a central role in that movie, culminating in the scene, in which Puss, Kitty and Humpty ride a magic beanstalk to find the giant's castle. In a Happy Tree Friends episode called "Dunce Upon a Time", there was a strong resemblance as Giggles played a Jack-like role and Lumpy played a giant-like role.The story appears in the 2017 commercial for the British breakfast cereal Weetabix, where the giant is scared off by an English boy who has had a bowl of Weetabix. A children's picture book, What Jill Did While Jack Climbed the Beanstalk, was published in 2016 by Sproodle Doodle Books. It takes place at the same time as Jack's adventure, but it tells the story of what his sister encounters when she ventures out to help the family and neighbors. JpgChildren's literature portal Horseshoe and devil.

SvgFolklore portal Flag of the United Kingdom. The item "RARE Children's 4 Book Set w Box 1931 Little Black Sambo etc McLoughlin Art Deco" is in sale since Thursday, April 5, 2018. This item is in the category "Books\Antiquarian & Collectible". The seller is "dalebooks" and is located in Rochester, New York. This item can be shipped worldwide.

- Binding: Hardcover

- Subject: Children's

- Topic: Literature

- Special Attributes: 1st Edition

- Country/Region of Manufacture: United States

- Year Printed: 1931

- Original/Facsimile: Original

- Place of Publication: Massachusetts

- Language: English

- Region: North America

- Publisher: McLoughlin

- Origin: US